The Plebeian International

Traditions of the Vanquished and the Future of Lost Causes

The Plebeian International aims to recover dreams and practices of institution-building among radical republicans in the mid-19th century – workers, women, abolitionists between France, Algeria, Brazil, Germany, and the United States – as contributions to a democratic theory beyond the nation-state.

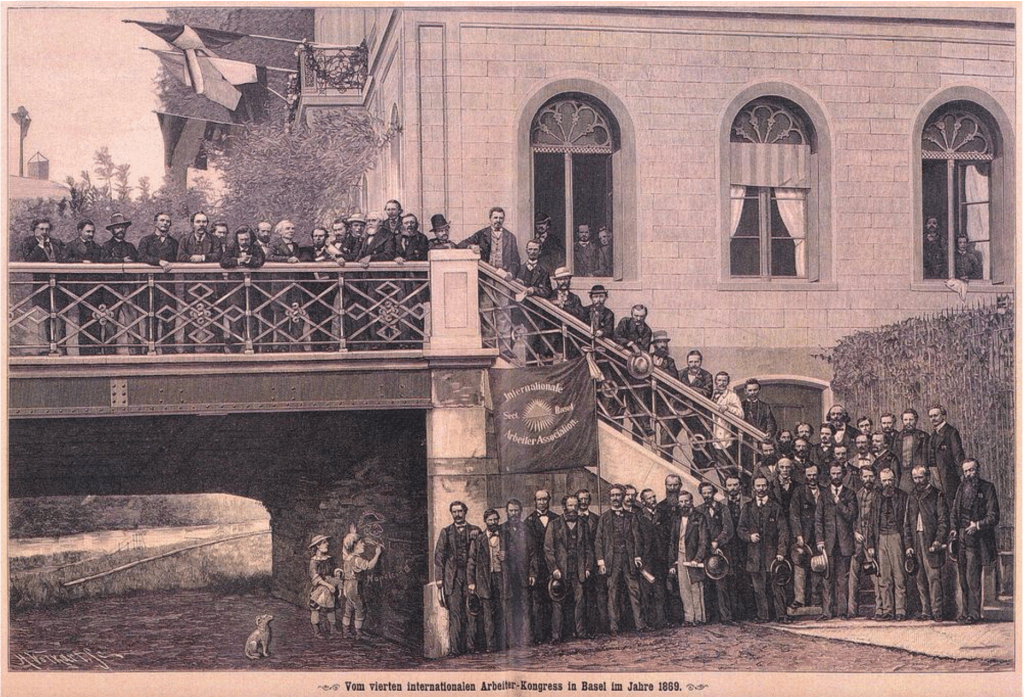

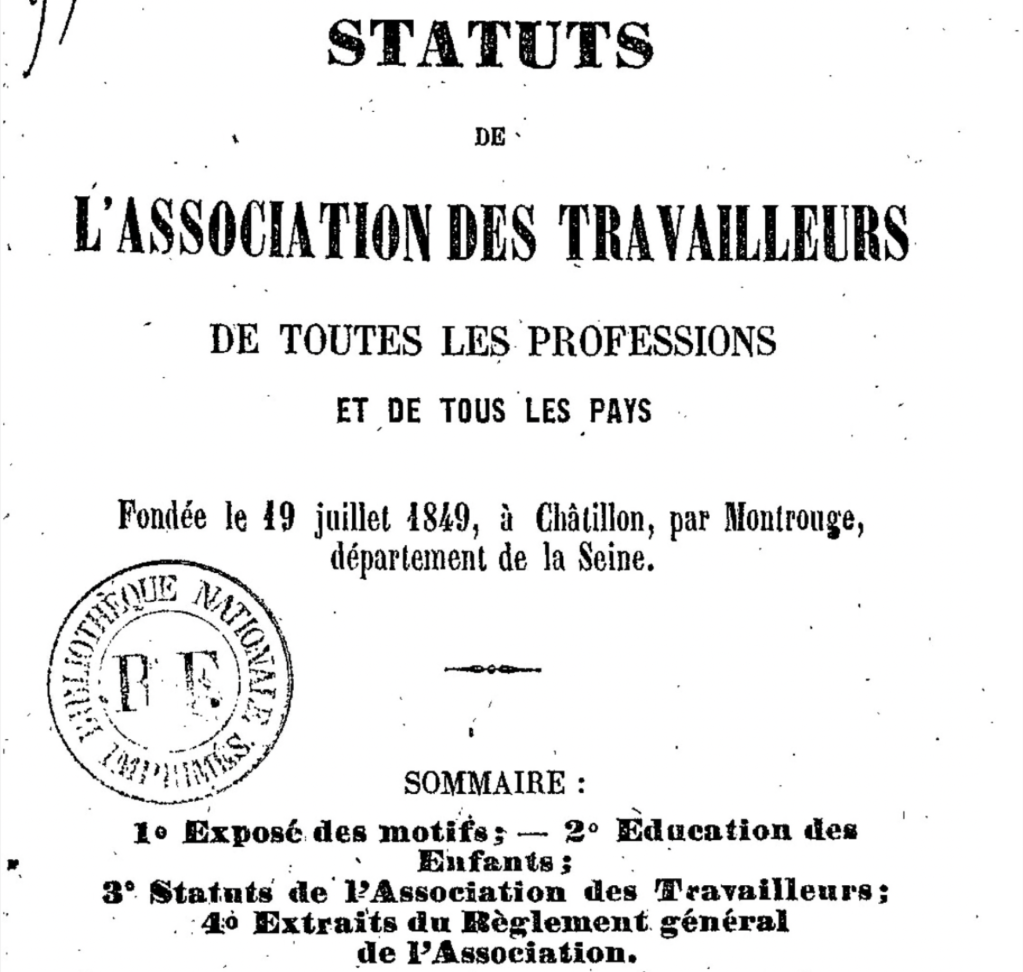

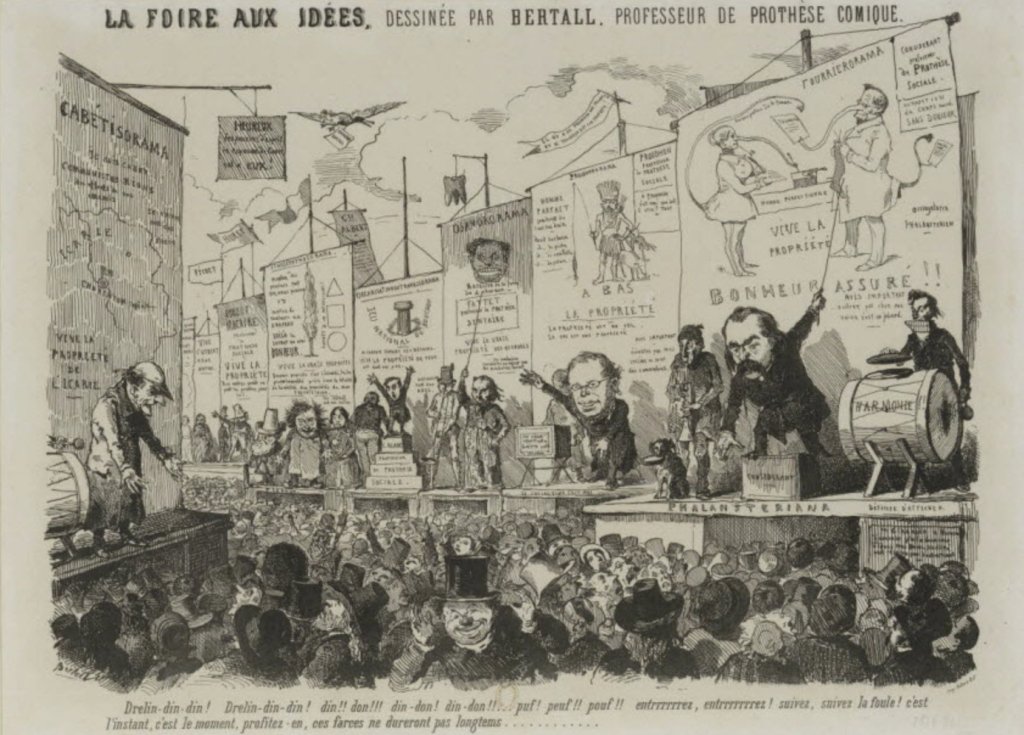

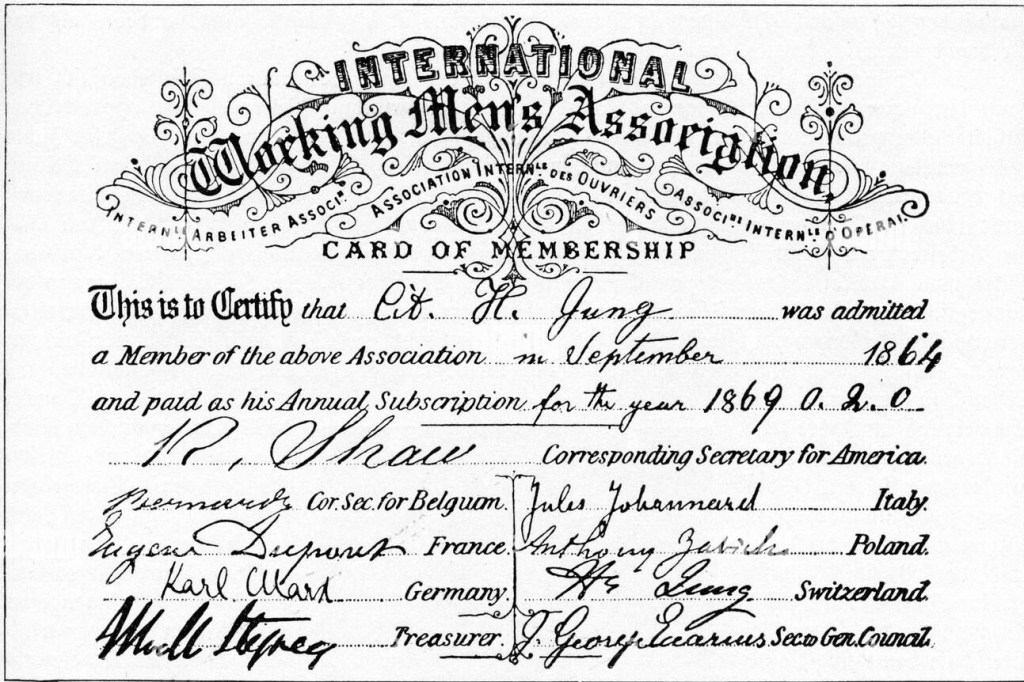

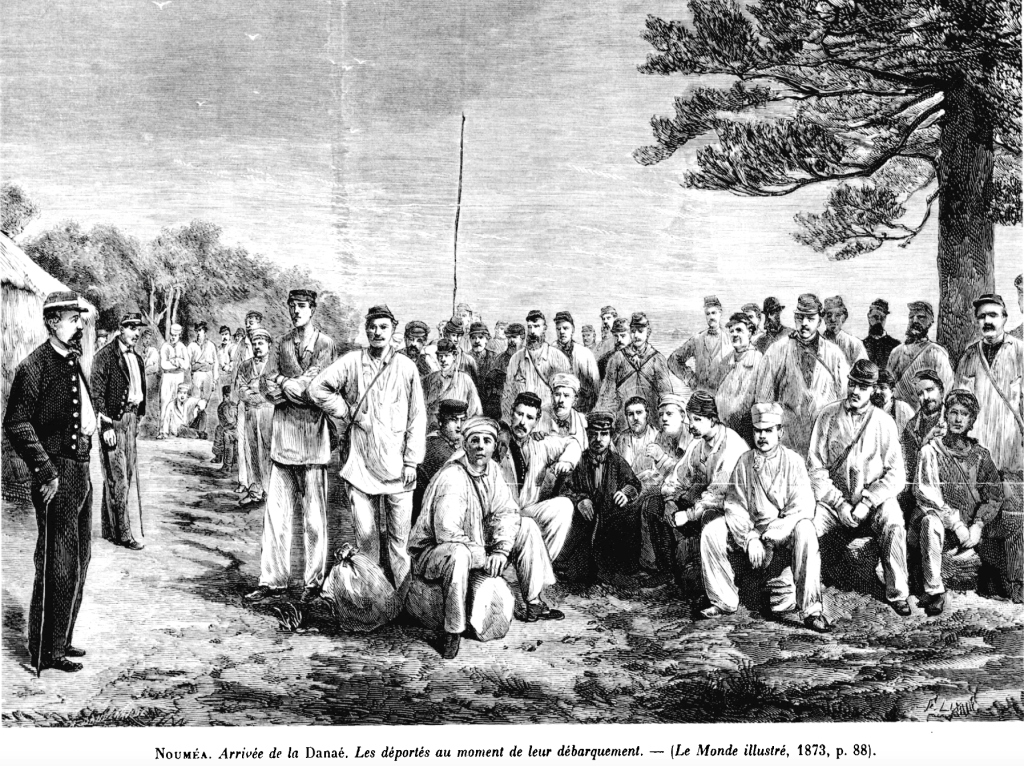

Between the 1830s and the 1880s, movement actors in the Atlantic world extended republican ideas of freedom, equality, fraternity, and civic virtue into both radically democratic and transnational registers. Variously labeling their projects as federalism, associationism, or communalism, these plebeian internationalists saw themselves involved in building a “universal republic,” which, far from an abstract utopia, they viewed as already emerging from within their movements. By recovering the histories of their defeated dreams – from the small and forgotten “Association of Workers of All Professions and All Countries” in the suburbs of Paris in 1849 to the epochal 1864 International Workingmen’s Association, the “First International” – I hope to expand our institutional imagination in the present, at a moment when social movements are again facing the challenge of envisioning durable institutional forms across national borders.

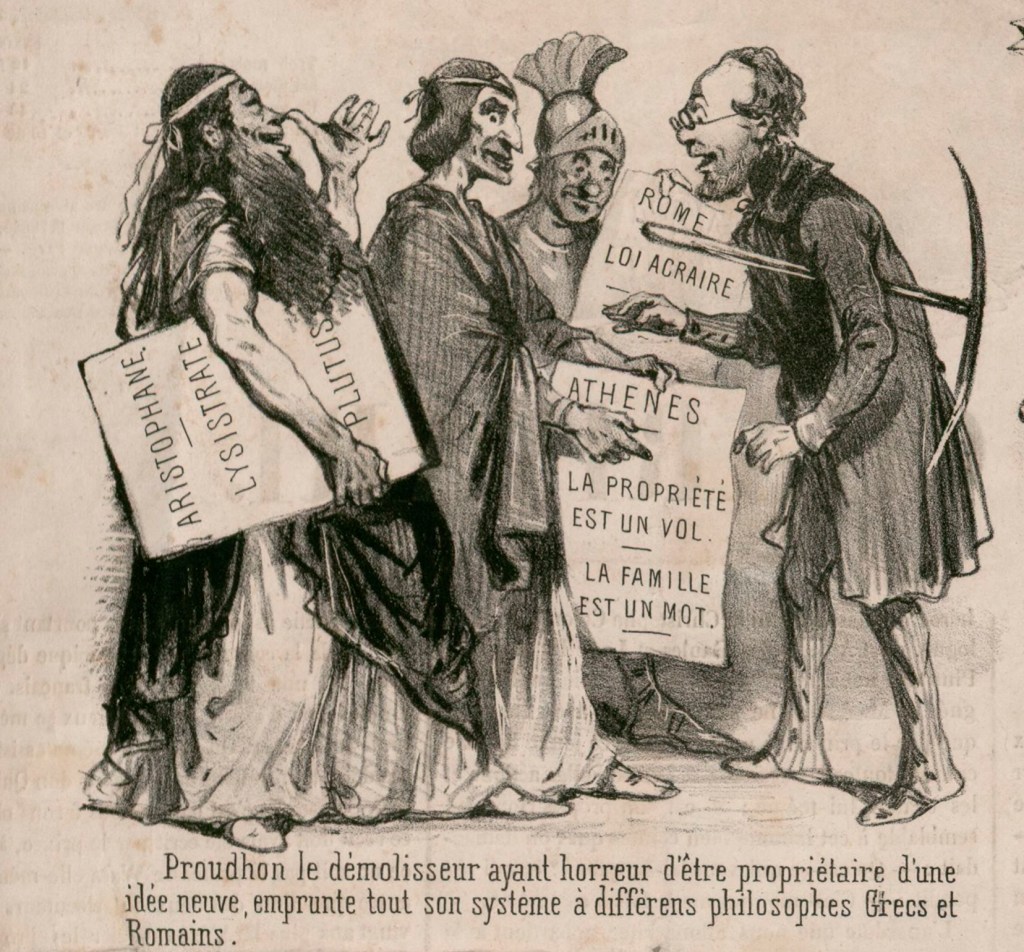

While my research is thus situated in the history of political thought, I do not turn to the 19th century as a matter of filling blindspots in the record alone. Instead, I center non-canonical thinkers from the margins of society as producers of theoretical knowledge in their own right. I do not read letters, journal articles, or manifestos by seamstresses, carpenters, typesetters, and formerly enslaved writers as mere illustrations of a philosophical framework but as generative responses to institutional challenges, wrestling with problems that continue to preoccupy theorists and movement actors alike. Not idealizing, but taking the plebeian internationalists seriously as democratic thinkers, I contend, helps us challenge the naturalized assumption that the nation-state frame best responds to the question of institutional durability for social movements in our own present. This is not a celebratory history: even the most egalitarian projects remained entangled in racialized and gendered visions of political order that require careful excavation. If one returns to the plebeian internationalists of the 19th century in light of the global capitalism of the 21st, their border-crossing revolutionary movements, once labeled “utopian” and defeated in their own time, might appear more realistic than ever: in their problems, their institutional projects, but also in the structures of domination from which they could never fully escape.

The 1848 Revolutions as much as the 1871 Paris Commune involved lively and innovative debates around the forms of freedom, equality, and fraternity. At stake was the possibility of institutions that would allow “the social movement” (le mouvement social) – as commentators referred to it in the singular – to move from the upheaval of insurrection to a durable republic. Their radical republicanism unsettled conceptions of the law as a constraint on action rather than a dynamic source of civic practice. Yet in their emphasis on institution-building and their internationalist imagination, the socialists and radical republicans of the mid-19th century contrast starkly with the “institution-blindness” and the nationally circumscribed populism that dominate theories of radical democracy today.

If you would like to read more about this research, please have a look at my article on the contested boundaries of “the universal republic” in the 1870 Algiers Commune (Commune d’Alger) and the 1871 Mokrani uprising, published in Nineteenth-Century French Studies (web/pdf).