The Insurgent Institution

Radical Democracy and Political Form

Contemporary thinking about social movements often seems stuck in a dichotomy between insurgent action and institutional form: of extraordinary acts of transgression that interrupt political order from time to time, before the streets are cleared and “politics as usual” can resume. For many movement actors, “institutionalized politics” has in turn become so closely associated with an unresponsive, elite-driven mode of decision-making that any idea of “radical democracy” would necessarily have to entail the critique of all institutional mediation. But what if this binary – with “radical democracy” as a flash in the pan and “institution” as a mere deadweight and constraint – was itself part of the profound crisis in our institutional imagination? And could there be ways to envision democratic action and institutional durability together?

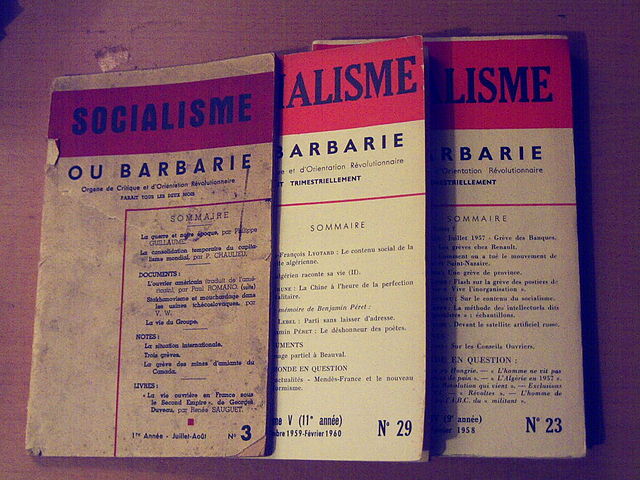

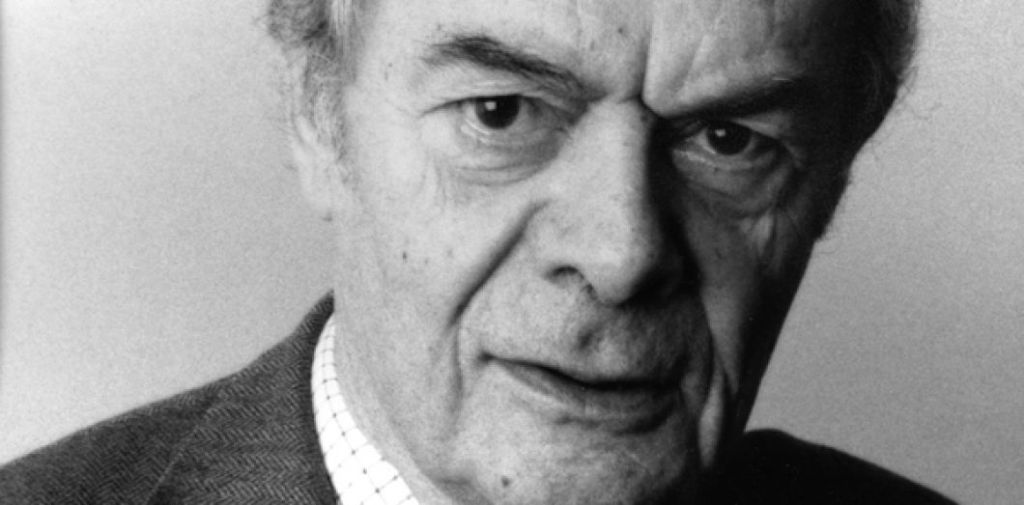

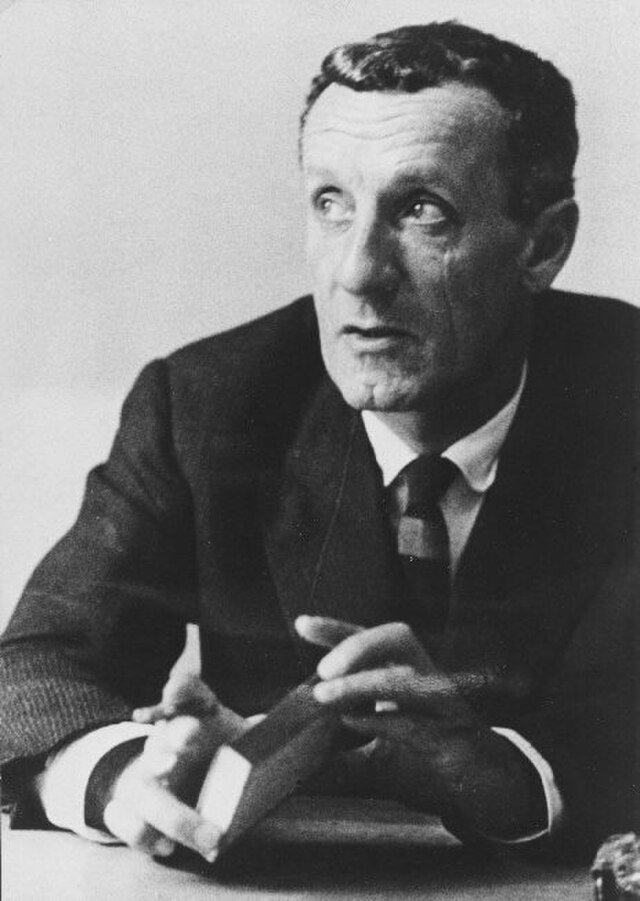

In L’institution insurgeante (The Insurgent Institution), an expression I borrow from Miguel Abensour (1939-2017), I engage with a tradition of 20th century French philosophy that often goes by the name of “radical democracy” – a current of thought typically read as anti-institutionalist. Theorists of radical democracy are said to celebrate “the political” (le politique) as a moment of rupture in opposition to institutional “politics” (la politique). While I do not doubt the impact such a framing has left on political theory, I show that it fails to account for the place that the concept of “institution” played in post-war French thought. More consequentially, reducing radical democracy to an anti-institutionalist project has blinded readers to the contributions that radical democrats can make to theorizing institutions beyond the abstract register of an “ontological turn”: from novel accounts of the symbolic dimension of law to concrete proposals of organizing popular power in participatory councils.

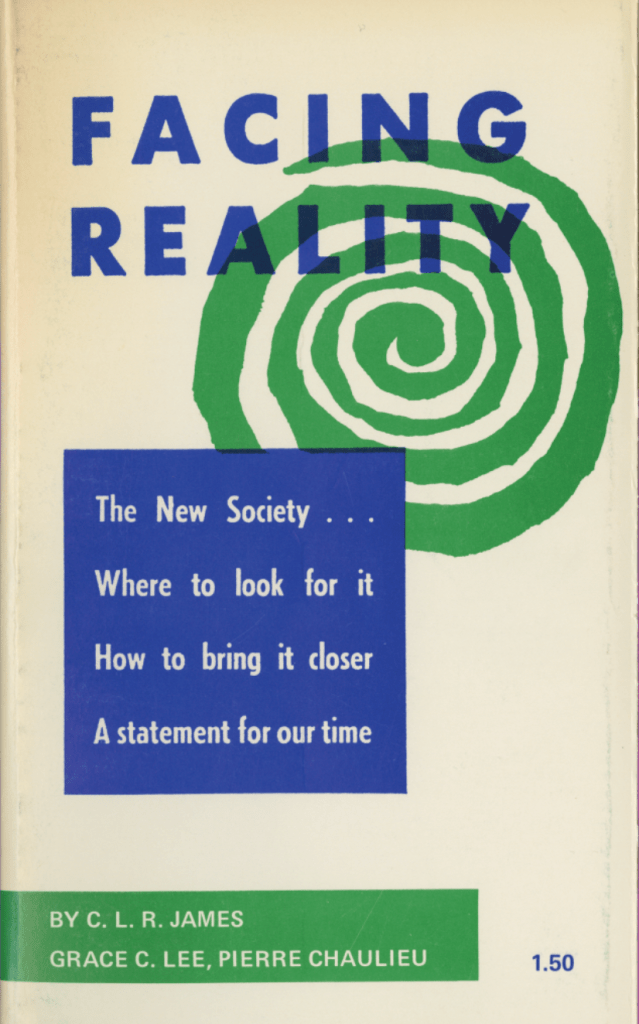

But rather than tracing various theories of “institution” in philosophical sources, L’institution insurgeante places theoretical developments against the backdrop of political problems. Beyond a Francocentric genealogy of radical democratic theory, I read thinkers like Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Claude Lefort, Cornelius Castoriadis, Grace Lee Boggs, C. L. R. James, and Miguel Abensour as part of a trans-Atlantic constellation of dissident Marxists who wrestled with the dialectics of praxis and institutional form and thereby paved the way for a new vision of democratic politics. Confronting the pitfalls of bureaucratic rule in the Eastern bloc and the challenges of anti-colonial struggles in the 1940s-60s, they set out to reimagine the relationship between transgressive action and institutional durability anew.

Drawing on archival research at theCastoriadis, and Abensour papers at Institut Mémoires de l’édition contemporaine (IMEC) in Caen, the Lefort papers at Humathèque Condorcet in Aubervilliers, and the C. L. R. James papers at Alma Jordan Library, University of the West Indies, Saint Augustine, Trinidad (in collaboration with Yuvan Dass), L’institution insurgeante offers the first global intellectual history of the radical-democratic “return of the political” in 20th century thought.

The dissertation, written in French, was supervised by Professor Frédéric Gros at Sciences Po Paris and defended on December 12, 2025. The jury consisted of Professors Justine Lacroix (Université Libre de Bruxellles, Belgium; présidente du jury), Hourya Bentouhami (Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès), Martin Breaugh (York University, Canada), and Oliver Marchart (University of Vienna, Austria).

For more on “insurgent institutions” in English, please have a look at my exchange with Massimiliano Tomba, published in Historical Materialism, 2022 (here) as well as my introduction to the Cornelius Castoriadis forum for the Journal of the History of Ideas Blog, 2023 (here).